How My Wife Single-Handedly Saved the Reputation of The National Lampoon, America’s Greatest Humor Brand

Thank you to Scott Rubin, Joe Oesterle, Sean Crespo, and Mason Brown for helping me get all the facts right!

In the aftermath of the most controversial election in U.S. history (objectively true since Trump is the first felon to be elected president), I thought you might need to read something completely insipid from my days at National Lampoon, a yarn with no redeeming qualities or insidious motives, but which nevertheless is completely true, about the time I nearly destroyed the reputation of America’s single greatest humor brand.

Here’s what happened:

The producers of the movie Boat Trip, starring Cuba Gooding Jr. came to my bosses at the National Lampoon and said they had just made this movie entitled Boat Trip, starring Oscar winner, Cuba Gooding Jr., and would the National Lampoon like to put its imprimatur on it, such that the movie would be re-entitled, National Lampoon’s Boat Trip, starring Cuba Gooding Jr.—after which a sizable pile of money would then presumably change hands in a fashion only lawyers understand.

For some reason, the higher-ups at the Lampoon left the decision to editor-in-chief, Scott Rubin, who opted to share the responsibility with the rest of the writing staff. They were screening the movie at a private theater in Westwood; we would watch it and decide if it lived up to the high standards of the National Lampoon in the year 2001. They’d already made the movie, so it’s not like we would have been able to punch it up or anything. It was a done deal. Take the movie as-is or don’t take it at all.

Rubin, had just one request:

“Nobody get high before the movie.”

He raised a finger and turned to me. “I’m not kidding,” he said. “This is a big deal. The very fate of the National Lampoon, the single greatest humor brand in American history, hangs on your good judgment. Your sober good judgment.”

Mason and Crespo couldn’t make the date, so the responsibility fell entirely on Joe and me. We nodded we understood the gravity of the situation. The pressure to keep my faculties intact was intense.

And yet I did not. For the following two reasons:

Reason #1: Raegan and I had only recently started dating, but I was already madly in love (we wound up marrying, and remain married to this day, so it all worked out). She was happy to join me for the screening, but suggested we celebrate by breaking-in her new bong. I hadn't mentioned Rubin's demand for level-headedness and didn't have the heart to tell her no. Besides, I thought Scott was being ridiculous. I was a lifelong student of comedy. Either the movie is funny, or it isn't. What harm could a little cannabis possibly do?

Reason #2: Working for a comedy brand is unlike working anywhere else. We were expected to be funny on command and all the time, even when it hampered productivity. We would regularly disrupt corporate meetings with our antics. When Rubin scored press passes to the floor of the 2000 Democratic National Convention, he and I rushed our way to the stage and unfurled promotional signs for the Lampoon website. Because nothing's funnier than getting thrown out of the DNC for holding up a poster of a disabled frog. Particularly when a troop of Girl Scouts is involved. At no normal place of business would it be considered okay to admonish the employees for not bringing weed to work (at least back then). But Rubin regularly complained. “What's wrong with you guys?" he'd say. "Back in its heyday, you’d open the door to the writers' room and a big smoke cloud would come billowing out like a Cheech & Chong movie!"

That was another thing. Everyone wanted the Lampoon to be as funny as it used to be, which wasn’t going to happen, not even with all the weed in the world. Because in the early 1970's its style of visually accurate-yet-tonally aggressive parody was brand new. There was no way my size 7W feet were going to fill the gargantuan shoes of Henry Beard, Doug Kenney, and Michael O'Donoghue. But since the Lampoon website predated social media, folks would email their complaints or literally yell at us over the phone. "Why aren't you funnier? Don't you assholes have any respect for the Lampoon name???" Sometimes we'd write back, "Dearest Sir, have you considered the possibility the Lampoon only seemed funnier because you were thirty years younger and super-high???"

Because the fact was, we did respect our roots. We pored over the early issues and modeled our material after old gags. We were trying to bring back the ballsy 70's sensibility, in a new, digital format.

So, when Rubin told us not to get high before the screening, and Raegan said, "Let's just get a little high," my brain weighed the outcomes and asked, “Ultimately, which was funnier? Which scenario would produce a story I would want to write about twenty years from now?"

The answer was obvious.

It's the night of the screening. Raegan and I are seated in the little theater and it's pretty packed with people and I'm already fighting to hold back my nervous laughter. I'd managed to avoid Rubin on the way in (he was busy schmoozing the Hollywood elite), but when we said hi to Joe (who I was shocked to realize had played by the rules), he assessed the situation with the speed and accuracy of an Interpol agent.

"You bastard," Joe said.

"Dude, what?" I said. "I'm totally fine. Anyway, don't tell Rubin. Promise me you won't tell Rubin..."

In the movie's first three minutes, Cuba Gooding Jr. and a woman named Felicia are the sole passengers of a hot air balloon he is apparently licensed to pilot, but which makes him so motion-sick that he projectile-vomits all over her. This is the least moronic moment in the movie. I don't remember any of this from the night of the screening, of course, but only from a regrettable Tubi re-viewing. Twenty minutes in, I'm wondering how they're going to sustain a blatantly and unapologetically homophobic premise for another full hour. And yet I know they must.

But this is not a review.

How high was I, you ask? So high that I laughed aloud more than once, which is not at all typical for me. So high, I believed the world would be a better place with more Boat Trip in it. I recall Raegan's disapproving glances, her grasp on reality somehow still intact. At some point, my brain did a flipee and I suddenly saw all the humor as ironic. Even in my muddled state, some primitive synapse in my noodle concluded it couldn't be possible for a movie this bad to get made, so it must be trying to be awful—on purpose.

Regardless of why I found it funny, I wasn't the only one laughing. The room erupted in laughter at every insipid, hackneyed, and offensive gag.

After the credits rolled, Rubin gathered Joe, Raegan, and me in the parking lot and asked what we thought.

I was the only one smiling.

"So, Joe," Rubin said, "What did you think?"

"I think you already know what I think,” he said, “and I can't believe you're even asking me. But you should definitely ask Brykman what he thought of the movie. Go ahead. I'm looking forward to hearing his answer."

Here’s what I said.

I said I thought the movie was "a meta, post-modern romp."

Joe shook his head. "It definitely wasn't. I'm not even sure what that means."

I doubled-down, "It played-off a bunch of classic tropes! Come on. A hot Swedish tennis team suddenly shows up in a lifeboat? Totally ironic, but fully aware of its own inanity. It was a tour de force the Lampoon should absolutely put its name on."

Scott suddenly looked panicked. He dropped his head in his hands, unsure of what to do. Could he possibly be wrong? Had he misread the movie?

”It stars Cuba Gooding Jr.!” I protested, “Oscar-winning actor, Cuba Gooding Jr.!!!”

"It was a monumental piece of shit!" Joe assured him.

"But how can I be sure?" Rubin fretted, distressed.

Left with no alternative, Joe suddenly broke. "Brykman's totally baked right now! Look at him, all smiley. Look at his eyes!"

"Joe!" I said, "You promised!"

"Dammit, Brykman!" Rubin said, "You nearly destroyed the reputation of the National Lampoon, America's greatest humor brand!"

"But it wasn't just me," I protested. "Everybody in there was laughing."

Joe said, "You idiot! You think those were regular people in there? They stacked the deck! They filled the place with ringers. Or else everybody was as high as you. Either way, the thing was rigged!"

Scott turned to Raegan. "You're the tiebreaker. What did you think?"

Without hesitation, Raegan said, "It was absolute garbage."

Rubin relaxed, satisfied he had heard everything he needed to hear.

"Thank God she came along," he said. "Stick with her, Brykman. She knows what's up."

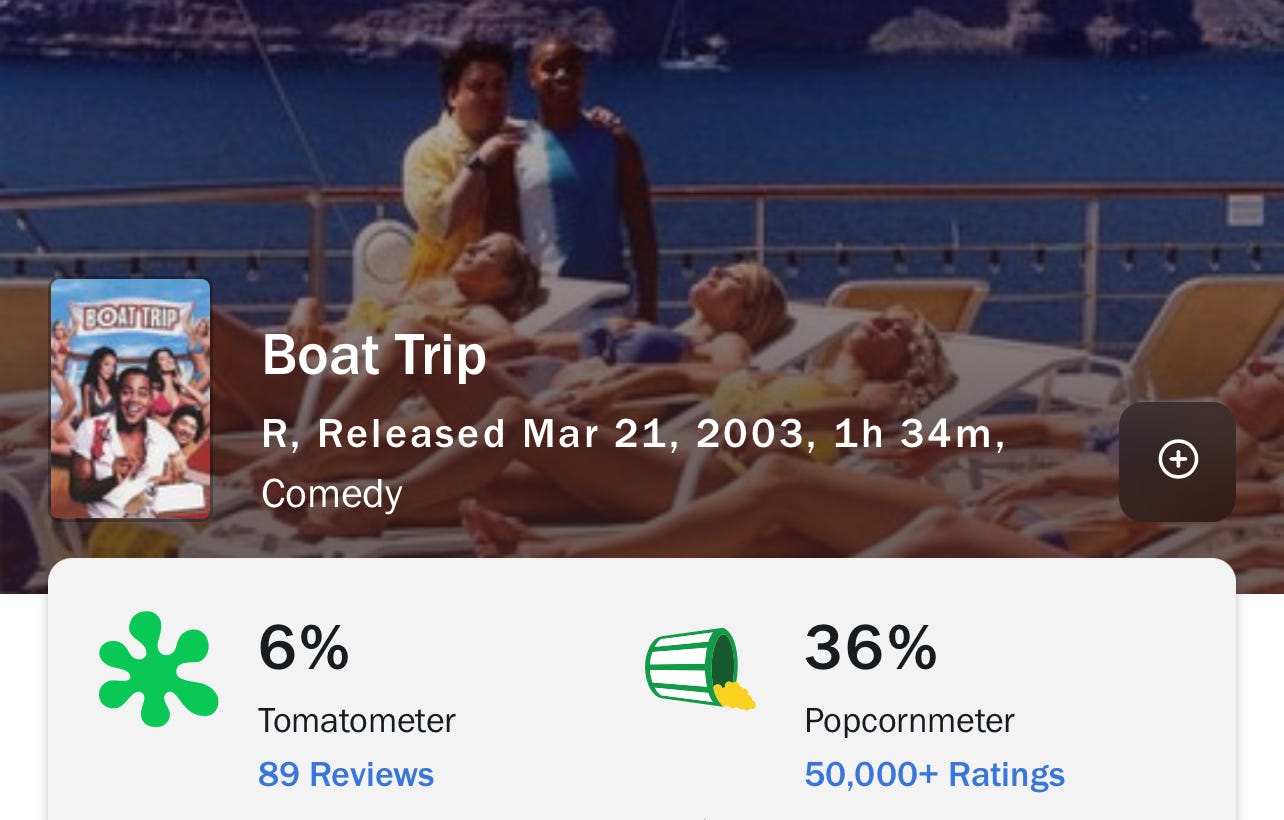

In his review, Roger Ebert wrote that Boat Trip was "made for nobody, about nothing...dim-witted, unfunny, too shallow to be offensive." On his list of the ten worst films of 2003, Boat Trip came in third.

To this day, it shocks me to realize how easily and thoroughly I had been duped—by inflamed passion, by THC, and by peer pressure—into believing a total pile of shit was worthy of the National Lampoon name. Perhaps there is a lesson here after all, an allegory for something going on in the US today—though it's anyone's guess as to what that thing might be.

Despite Rubin's bitter tone, I detected a glint in his eye and sensed he was proud of his fellow Jew-editor. Because even though I had travelled the path that risked destroying the reputation of the National Lampoon, America's greatest humor brand, he knew deep in his heart that I had in the end correctly chosen the funnier path.

And that has made all the difference.

Hilarious. It's always hard for a goodhearted person to have to respond to total schlock that you know dumb people worked hard on.